Larry’s Father’s House

A Small Town in the Midwest

Larry, his father and Lenny retired to the living room from the kitchen, where they had just finished a dinner of Dad’s specialty, great northern beans and pork. Larry had been eating this dish, as prepared by his father, all his life, and while he liked it (its consumption still constituted Larry’s only recorded use of ketchup), it still tended to make him burp.

It was a week or so before Christmas, and Larry and Lenny were in town to host a reunion at Larry’s high school. Christmas isn’t the usual time for high school reunions, of course, but it’s a small high school, and the time between Thanksgiving and Christmas was the slowest time of the year in Vegas, The Regular Guys show shut down in early December until things picked up again the week before New Years.

After the show, Lenny would go spend the holiday with Ann and his family, the first time Ann would accompany Lenny to his parent’s house for the holidays, a prospect that made him as nervous as Larry was nervous about hosting a show in front of people he had known as a kid.

In anticipation of his only child’s first visit over the holidays in several years, Dad had purchased a tree, had it delivered to his house, removed the boxes of decorations and had even begun to decorate before giving up and deciding to await the reinforcements provided by Larry and Lenny.

After entering the living room, Dad and Lenny went immediately to two leather wing chairs near the fireplace and sat down next to a small table that held a bottle of port and three glasses. There was a fire going, some candles lit, dozens of Christmas cards on the wood-paneled walls and some Christmas carols playing in the background. Like the rest of the house, it was a gracious and inviting place, even if it hadn’t seen a woman’s hand in ages.

Larry accepted a glass of port from his dad even though he still would prefer not to drink in front of him, before dispatching himself to a large box on the floor in front of a partially decorated Christmas tree.

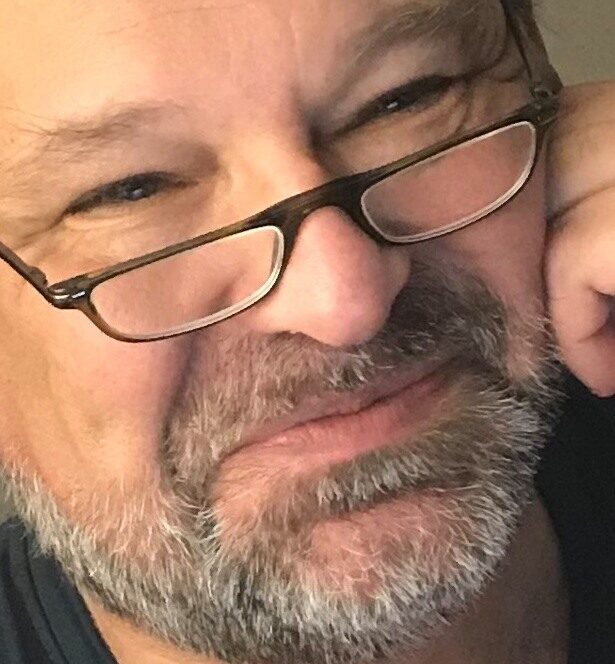

Unlike his son, who had taken a while to find his calling, Dad had found his early in life. He knew from as long as it was possible to know that he would be a minister and, in fact, had found no reason to leave the church he was baptized in, having served it as choirboy, usher and acolyte before leaving for school and returning to serve as vicar, associate pastor and pastor. He had been open to moving to another town closer to his wife’s home state, but then his wife died when Larry was nine and, otherwise happy, he decided to stay until he had retired several years ago.

Larry began sorting through the decorations. There was the usual assortment of decorations a family would have acquired over the years: lights, tinsel and ornaments, some bought and some handmade. There were now enough to insure that Larry would end up having to decide what made it on the tree and what didn’t.

Dad and Lenny sat quietly. They had seen each other several times over the years and had always gotten along well. Lenny enjoyed the good conversation the retired reverend provoked and had even enjoyed his first experience with great northern beans and pork despite Larry’s warnings, and he was looking forward to a quiet evening of good company. It would be an interesting contrast to the usual zoo his family’s holiday gathering was.

“Lenny, you still seeing that cute cop?” Dad asked after a few moments.

Lenny nodded and smiled.

“Actually, she’s assistant chief of police now and is responsible for the day to day running of the department. And she’s got both a law degree and a management degree now.”

“Dear me, a law degree and a management degree? Larry, did you hear that?”

Larry nodded and smiled to himself.

“Of course I knew that. I was at her graduation.”

Larry thought it interesting the habits you fall into when you return to the house you grew up in. As a Lutheran child Larry was accustomed to speaking only when spoken to, and, even then, you said as little as possible.

And Larry had spent every Christmas as a kid doing just what he was doing now, sorting out the tree decorations. Early on there had been help from Mom and Dad, but after mom died Dad was content to delegate that duty to Larry and retired to the same place he was sitting now. After a while, the minister’s tree trimming had become a modest event on the congregation’s social calendar and later tonight there would be no shortage of dad’s former parishioners stopping for visiting or caroling, or, if they were feeling particularly sociable, both.

Larry smiled to himself and thought he was glad to be where he was.

“Is she still as pretty as ever?” Dad asked.

Lenny nodded affirmatively and Larry whistled.

“So,” Dad said. “She’s pretty, educated and a professional success?”

Lenny took a drink of port and nodded vigorously.

“Why’s she still seeing you then?”

Lenny laughed and put his drink on the table.

“You know, it’s a mystery to me, too, sir.”

“It’s a mystery to all of us,” Larry said drolly.

“Larry, do you talk to Rachel at all?” Dad asked; he was fond of Racel and had taken their breakup harder than Larry did. Privately, he had wanted to tap Larry on the head with a rubber mallet when he had let her get away.

Larry looked up; he knew his dad had been very fond of Rachel, though he had no idea Dad had wanted to hit his head with a rubber mallet.

“Periodically. Every now and then we exchange emails. We haven’t talked for ages.”

“She sent me a Christmas Card.”

“Really?” Larry sounded surprised. Dad had met her only a couple of times.

Dad went and took a card off the wall and handed it to Larry. The card was eggshell white, with a painting of the vice president’s residence in a very holiday-esque scene on the front. There was snow and a large decorated tree and carriages and people walking around and a bright star in the evening sky. There was a printed greeting inside, as well as several handwritten lines in handwriting Larry recognized as Rachel’s.

“I got one, too,” Lenny said.

“You too? I didn’t get one”

Which was true. Larry had, however, gotten a Christmas card personally signed from the president himself, and the president was known to sign personally only a handful of his Christmas cards every year. A disgustingly popular president winding up his second term, those who received them prized them. Rachel had also sent Larry a personal card, as well.

“She was a good lady,” Larry said.

“Yeah, she was,”

Though his dad had only spoken three rather non-committal words, Larry knew it was an invitation to expound if he wanted.

“A great lady. A great lady at the wrong time, perhaps.”

Larry wasn’t the only Lutheran in the room and Dad left it at that. His was not to pry; Larry had told him basically the same thing before, and if that was all his son wanted to say on the matter, then that was that. That didn’t lessen his desire to want to tap his son on the head with a rubber mallet, however.

After a few minutes of digging, Larry made a sound as if he had discovered oil. He did a little more digging and pulled out a five-pointed star, made of cardboard and covered with aluminum foil. Obviously hand-made, the foil had started coming off in places. Larry held it out for inspection.

“Boy, look at this thing Dad,” he said enthusiastically. “You remember this?”

Dad smiled.

“Of course I do,” he said getting up and walking to his son. Larry handed the star to him and he looked it over fondly. “You were three when we made this.”

“Really?” Larry asked, too young at the time to have remembered it. “Were we also blindfolded? This looks like it was made in the dark.”

Both Lenny and Dad laughed; the ornament was star-shaped only in the most technical description of the term; it did have five points but some of the points were longer than the others and while it looked pretty much like a star when hung right side up, turned any other way it more resembled a sales chart of a company of recently fluctuating fortunes.

“It was our project one day while your mother was out running errands. We needed an ornament for the top of the tree. You actually did most of the work; you drew the design and taped the foil to it. All I did was cut the shape out of the box and pull the tape out of the roll.”

“I haven’t seen this for years,” Larry said. “It’s held up pretty good.”

“They made tinfoil pretty strong back then,” Dad said.

Dad handed the star back to Larry and the two smiled at each other.

“You know Lenny, we should probably pitch in if we want to get this decorated before Lent.”

Dad, who always fancied himself a handyman despite mountains of evidence to the contrary, sat on the floor and started untangling the lights, which itself was indictment of his unhandiness: every year he pledged to roll up the lights so they would unroll easily and not need to be untangled, and every year he didn’t.

Larry knew better than to be in range when dad was untangling lights and took his glass of port and sat down in the seat vacated by his dad. Lenny stood with his hands on his hips, thinking it would take ages to get this mess sorted out. Dad, however, had decades of practice at this, and had it untangled in rather short order; and, starting at the bottom, he and Lenny began putting up the lights.

“So Lenny,” Dad said after a few minutes. “Are you finding money an awesome master?”

Dad sounded genuinely concerned.

Lenny sighed and considered the matter for a moment. The Regular Guys were now wealthy men. Not Gates or Buffet wealthy, but by any measure, certainly the measure of a retired Lutheran minister, they were men of substantial financial means.

“No, but we easily could,” Lenny concluded. “And actually, by some standards, we’re not even all that obscenely paid. But we make enough where I can see where too much money could cause problems, just like too little money causes problems.”

“I’ve seen that, even in a relatively small parish like we have here,” Dad said. “Larry, you remember the Raymond family?”

Larry said that indeed he did. His first tentative, clumsy kiss had been with a Raymond daughter. So had kisses two through seven, inclusive.

“Well, Mr. Raymond made a pile in real estate around here, a lot faster than he had intended to really,” Dad said. “His kids were spoiled to begin with, though I’ll deny ever saying that, and wanted this and that, and he gave it to them. Then his wife wanted things, and they bought the big house on the golf course. Then he started wanting things, and in ten years he hated everybody in his family and the feeling was fairly mutual. And he had income tax trouble, too.”

“I never knew that,” Larry said.

“It was a fairly open secret. You were a kid then, worrying about other things, like the Raymond daughters.”

Larry laughed and got up and returned the vice-presidential Christmas card back to the wall.

“That was an interesting observation you made about money being an awesome master,” Lenny said after a while. “There is a tendency to want to do things with it. Things you normally wouldn’t do, like buy ten cars at one time.”

“You’ve wanted to buy ten cars at one time?” Larry asked. “I didn’t know that.”

Lenny nodded.

“Yeah, fairly often, too. This is funny for a couple of reasons. One, I’ve never spent a whole lot of time fantasizing about cars. I mean cars are nice, but back when I couldn’t afford ten cars, I never lost a whole lot of sleep dreaming about having ten cars.”

Lenny paused to enjoy a sip of port. It was good port and Lenny was quickly turning into a big port fan.

“Plus,” he said, continuing. “We don’t really use the two cars we have right now a whole lot.” Lenny was referring to the Jaguar he had bought for himself and Larry’s Mazda Miata

“Well, that’s what limos are for,” Larry said.

“Limos!” Dad exclaimed.

“Sure dad. The hotel actually provides them, so we can blow our money on things like gambling and chicks.”

“Sometimes at the same time,” Lenny said, smiling.

Dad laughed. He’d had no idea how Lenny had been handling his newfound wealth, but he knew from conversations with his son that Larry was taking his more or less in stride and was glad to have raised his son to graciously and patiently bear both his success and the bumps in the road that occurred along the way, and would occur in the future.

“Well, it’s good to see you appear to be keeping things in perspective,” Dad said. “Fortunately Larry and I were spared both extremes while he was growing up.”

Lenny and Dad had completed putting the lights up and Lenny returned to his seat while Dad went to the kitchen for a cheese plate he had made up just for the occasion. He put it on the table, sat down, and poured more port. Lenny joined him while Larry took over tree trimming duties.

“It helps,” Lenny said, “that we don’t do this for the money. All we really want to do is a good show the next time we take the stage.”

“Larry’s said that on more than one occasion.”

Larry stood attending to his tree-trimming duties, as usual content to let others do the talking; he kept his ears open though, just to make sure they didn’t say anything bad about him.

“It’s funny,” Lenny said. “The money used to be really important back when I first started. It’s what I used to dream of. And notoriety. And I got very little of either. Since abandoning hope though, we’ve got both in busloads.”

“We don’t work for free though,” Larry said, chiming in from the peanut gallery.

“Well, we are tomorrow night,” Lenny said.

“You’re not charging the reunion committee an obscene fee?”

Lenny laughed.

“No, Larry got talked into donating not only his talents but mine as well,” Lenny said smiling.

“Getting a Lutheran man to volunteer for something isn’t the most difficult of tasks,” Dad said. “Though I’m surprised he volunteered your talents; that’s quite an imposition.”

Larry waved a hand as if it was nothing.

The doorbell rang. Larry’s dad went to answer it, and soon the voices of a dozen or so carolers could be heard from the porch. They were the first of a handful of visitors who would come the rest of the evening.

Marge’s Coffee Shop

Corner of Main Street and the County Highway

A Small Town in the Midwest

It hadn’t been a very long walk from Larry’s father’s house to Marge’s Coffee Shop, even though Marge’s Coffee Shop was all the way across town. The walk, which had not been vigorous, took less than three minutes. Down Maple Street to First Street, then up to Main Street, then down Main Street to where it met the county road that led to the U.S. highway.

The only apparent acknowledgment that the 21st century had arrived on Main Street was a video store and even that was housed in a building built fifty years ago. The post office, built in the early 1970s to replace the one built around 1910, was the newest building on the street. The citizens of Larry’s town didn’t build often, but they built to last, and everything else was much the same as it had been when Larry had left for college: a hardware store, the adjacent farm implement store, the library and a small grocery store as well as several other small shops. The big box stores had bypassed the town in favor of a slightly larger town on the interstate a few miles away.

Marge’s Coffee Shop had been around since before The Depression. Larry, and his father for that matter, had been eating there all their lives.

And not much had changed; the front window still had stickers announcing that BankAmericard and Master Charge were gladly accepted.

There was a counter with eight stools on the left and four booths along the wall on the right and a half dozen tables in between. A small salad bar was located in the back, and behind that was a larger room with a dozen more tables. The place was almost empty; lunch hour had passed and customers wouldn’t begin filing in for dinner for a while.

“Larry, Larry, Larry!” a loud, deep, feminine voice proclaimed.

A rather stout, buxom woman in her 60’s barreled out of the back room.

“Marge!” Larry exclaimed as he allowed Marge to give him a bear hug, not that he could’ve prevented it had he wanted to.

“Look at you, a big star now. And Lenny, look at you,” she said familiarly, as if she had attended Lenny’s birth and was not laying eyes on him for the first time. “We’re so glad you could come and co-host the reunion tonight.”

Lenny said he was glad to be there, which was true enough.

Marge’s real name was Doris, but she had been called Marge since she and her husband had bought the place ages ago from the original Marge, who had opened it along with her husband. The current Marge’s husband had died while Larry was still in high school. They were childless and since Marge had fed Larry more meals than any other woman, she could be forgiven for feeling like a son had returned.

“You know Larry, I made your favorite dessert,” Marge said. “Your dad was in for coffee this morning and said you might be by.”

That wasn’t a bulletin; dad was always stopping by for coffee. It was how he kept up on the news of his former parishioners since his retirement; plus he made lousy coffee.

Larry and Lenny sat down at the counter, Larry’s favorite place. It didn’t really matter where on the counter, he had sat in every seat a hundred times, but Larry always liked the counter. Instinctively, Marge produced a cup of coffee for Larry and asked Lenny if he wanted one. Lenny did.

“So, how long has it been since you’ve had my chicken fried steak, young man?”

Larry laughed. He enjoyed being called a young man.

“Too long, Marge; several years, probably.”

“World famous chicken fried steak for you Lenny?”

Lenny was faced with a tough etiquette dilemma: he despised chicken fried steak. He would hate to come to a piece of Americana like Marge’s Coffee Shop and have something he wouldn’t like; he really wanted a burger.

“You know, you can’t get a decent burger in Vegas, Marge,” Lenny said, lying through his teeth. “I’d like the biggest one you make, with cheese, bacon, mayo and some onions.”

“Lenny, Marge’s biggest burger will kill you; not to mention two cows.”

Lenny laughed. “I’ll take that chance.”

“Fries, too?”

Lenny nodded.

“Make them extra crispy, Marge; he’ll love’em.”

Marge smiled fondly; little Larry had been notorious for liking his fries extra crispy.

“So what are we going to do tonight, partner? Did they say what they wanted?”

Larry waved a hand. “A few laughs, pass out some silly alumni awards; stuff like that.” Larry had been dreading this gig, but now that he was back in town he was feeling better about it and was, in fact, looking forward to it.

“You gonna ralph like you did that one time? That was cool.”

Larry laughed.

“Probably not. I should be okay.”

(Two)

As the pair stood outside Marge’s Coffee Shop belching, Lenny, by now completely in love with small town America, decided he wanted a haircut.

“I haven’t had a real barber cut my hair in 20 years,” he said.

Larry laughed nervously. He had spent a good portion of his childhood having his hair butchered at the local barbershop and tried to stop Lenny but Lenny was determined.

So they walked down Main Street a bit till they came to a storefront with a barber pole out front. There was a sign on the window welcoming everyone to the Four Day Family Barber Shop. Beneath the sign the four days of the week the barbershop was open were painted on the door. Larry’s dad had been the first one in town to say the Four Day moniker represented the amount of time it took for one’s hair to recover and look somewhat presentable after walking out.

Larry walked in first to a nice welcome from Wally and Gordie, the two brothers who had owned the Four Day Family Barber Shop for ages.

“My friend is in need of a haircut,” Larry said. Larry himself had taken care to insure he did not need a haircut this trip. He would’ve cut his hair himself to insure that.

“Well, sit down then young man,” Gordie said, motioning Lenny to his chair.

Lenny sat down.

“You want a trim,” Gordie said. It wasn’t really a question.

“Uh, yeah, a trim sounds great,” Lenny said; both Larry and Wally laughed.

“It wasn’t a question, Lenny,” Larry said.

“What?”

“It wasn’t a question,” Larry repeated. “You’re getting a trim.”

“We could shave your head, if you’d like,” Wally said.

Lenny shifted in his chair.

“No, no,” Lenny said, not as nervous as a Vegas headliner accustomed to expensive hair stylists probably should’ve been. “A trim is great. Larry, do we have time? What time’s the show?” Lenny looked at his watch.

“Now, don’t you go fretting about that,” Wally said. “You got lots of time; besides, Gordie will have you outta here in a jiffy, won’t you Gordie?”

Gordie grunted; he was ready to go.

“Just make me look handsome,” Lenny said.

“Ooh, that’s going to cost you extra, Lenny,” Gordie said.

“A basic haircut can only do so much, Lenny,” Wally confirmed.

Larry waved a hand.

“Go ahead,” he said. “We’ve got a long term deal, he can afford it.”

Gordie got to work and Larry and Wally chatted amiably.

“Larry, you sure I can’t give you at least a touch-up?” Wally asked. “It’s a big show tonight.”

“No, no Wally. I got a trim last week. I wasn’t planning ahead I’m afraid.”

“Kids,” Wally said, shaking his head. “Always living for the moment. Does your fancy-pants Vegas barber have a nice assortment of dirty magazines in the back room?”

Larry laughed. Wally’s magazine collection was well known amongst the men of town, some of whom seemed to stop by for daily trims.

The haircut was quicker than you’d think it would be, sort of like an execution, and, Larry had to admit, not too bad, for Gordie. Larry had seen, even worn, worse over the years. Still though, Lenny’s hair looked like badgers had just attacked it.

“Larry, I can’t go on stage like this!” Lenny announced when they were safely out on Main Street. “I look like, like…” – Lenny paused to glance at his reflection in a storefront window – “is Gordie blind? I mean, seriously, isn’t there some sort of sight test for barbers?”

Larry laughed most of the way home. When they walked into the house Larry’s dad greeted them.

“Oh no,” he said. “You took him to see Gordie, didn’t you?”

“He insisted, pop. I tried to stop him,” Larry said. “He said he wanted a real, small-town haircut.”

Dad stood with a hand on his chin and regarded Lenny and started laughing.

“I’d say he got one,” Dad said nodding.

“You’re lucky you’re a man of the cloth, sir,” Lenny said running to the bathroom.